Wildflower Garden

Gardening for Wildlife – Tips from our in-house Ecologist

Website & Media Assistant (and trained Ecologist)

26th January 2023

January

Winter is a great time to add a pond to your land, allowing it to fill naturally with rain water and be ready in time for the first signs of spring! Adding a source of water is a wonderful way to increase biodiversity value, and it is incredible how quickly wildlife starts to arrive, as we witnessed last spring at Naturetrek HQ. Ponds support reptiles, amphibians and a plethora of insects, as well as offering a drinking source for birds and small mammals. Bats forage off the surface at dusk, which can be a wonderful spectacle to watch. Even a tiny feature such as an old washing up bowl buried to its rim, filled with rain water and an oxygenating plant plus some native marginal plants can be of great benefit (always include an escape ramp for small animals, such as a few partially submerged rocks).

February

Clean your Bird Feeders

Bird feeders are becoming an increasingly popular feature in households across Britain, with an estimated 64% of households participating in feeding birds in their gardens. This is a brilliant way to connect to nature and to find out what species are living on your doorstep, but in the age of avian disease outbreaks such as Bird Flu and Trichomonosis, it is becoming very important to keep bird feeders clean.

Avian flu is a virus that is usually transmitted from one bird to another through droppings and saliva. The most severe outbreak of the disease recorded in the UK occurred in 2021/2022, killing many thousands of wild bird species. Although the majority of these are seabirds and waterfowl, garden passerine birds are also affected and can transmit the disease, which is where cleaning our bird feeders is becoming increasingly important. Having spread from Scotland, Avian Flu has extended along the English coastline, reaching Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, as well as Wales and Northern Ireland.

Trichomonosis is a disease caused by a parasitic Protozoan known as Trichomonas gallinae that affects the digestive system of birds. It can impact various species, but has been particularly damaging to Greenfinch populations since 2005 when the disease emerged. It is estimated that the Greenfinch population has halved since then, with Trichomonosis being a major contributing factor. Chaffinches have also been significantly impacted by the disease and infections in House Sparrow, Dunnock, Siskin and Great Tit have been recorded according to the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO).

Effective cleaning of a bird feeder to reduce the risk of these diseases spreading can be achieved by using a 5-10% disinfectant solution to remove droppings, saliva, regurgitated food and old moulding food from the feeder and immediate surrounding area. Droppings and saliva are the main avenues for these diseases to spread and must be removed. To avoid the accumulation of droppings in a specific area of the garden, the RSPB suggests rotating the position of bird feeders after being cleaned (https://bit.ly/3QAUXVF). It is ideal for feeders to be cleaned as frequently as possible to prevent the spread of disease, ideally every day. Droppings can also accumulate in bird baths and therefore it is equally important to clean them as well. Finally, remember to protect yourself when cleaning feeders by wearing gloves and ensure brushes/cloths are disinfected after use.

Install Swift Boxes

The Swift has recently been added to the IUCN’s Red List, recognising that the species is now of ‘highest conservation concern’ in the UK. Fortunately, there is much we can do to help support this iconic summer migrant!

Swifts are void nesters, often utilising internal spaces in buildings such as lofts, soffits and wall cavities. Modern buildings are usually very well-sealed, however, and renovation works to older structures often block nest access gaps. A Swift box is a great way to provide a permanent nesting option; locate your box at least 5 metres above the ground with a clear drop beneath, ideally sheltered along a building’s eaves or beneath an overhanging roof. Swifts arrive on our shores around April, so installing Swift boxes now will ensure they are available for use this breeding season (although it can take a while for them to be found by birds).

March

Help Solitary Bees (with bee hotels, earth mounds and wildflowers)

Bees are often considered creatures that live in colonies, such as the familiar Bumblebees and Honeybees. However, these social bees make up less than 10% of the bee species in the UK. The remainder (around 250 species) of this diversity comprises solitary bees, which, as the name suggests, includes species that live in a nest for one.

Among the first solitary bees to emerge in March are Hairy-footed Flower Bee and Red Mason Bee. Both species will benefit from artificial ‘bee hotels’, which provide a series of wooden/bamboo tubes ideal for these bees to nest in. When setting up a bee hotel, it is best to position it in a roughly south-facing position, approximately a metre above the ground with no foliage blocking the nesting entrances.

Naturally, solitary bees live in habitats such as grassy embankments, riverbanks, cliff faces, moorlands and open woodlands, where they utilise loose/sandy soil to dig burrows, or crevices in rock/log piles. These habitats can be mimicked on a smaller scale in one’s garden by creating earth mounds, bare earth patches and rock/log piles in full sun. It is important to ensure that the soil is not too compacted for the bees to dig in – a mixture of sand and earth can provide suitable digging substrate, or a hole can manually be ‘poked’ into compacted earth for the bees to enter.

Due to their incredible diversity, solitary bees are key pollinators and planting suitable species as nectar sources in March is another way to attract them throughout the season. Leaving a section of your lawn to grow will inevitably promote the growth of various dandelions, daisies, buttercups and other wildflowers which are frequently visited by solitary bees. However, species such as Common Toadflax, Wild Parsnip, Hawkbits and others can also be planted. See https://bit.ly/3XadcmF for more bee-attracting plants.

April

Tip 1: Control Pests Naturally

A gardener’s never-ending battle against plant-eating invertebrates, such as slugs, has always taken place in Britain. These animals are often described as ‘pests’, but are native, wild species in their own right that form an important component of the ecosystem.

Gardeners often resort to chemical weapons in the form of slug pellets and the like, but these substances can be consumed by many other species and lead to unintentional poisoning. So why not encourage species that predate these ‘pests’ to colonise your garden? Hedgehogs, birds and native rodents often get credit for eating garden ‘pests’ and rightly so, but by enhancing your garden for reptiles and amphibians you’ll add an additional string to your bow – many reptiles and amphibians predate invertebrates such as slugs and our native Slow Worm, Common Frog and Common Toad are no exceptions.

The easiest way to attract the latter two is to create a pond in your garden. Even a 1m x 1m square pond is enough to attract Common Frogs, whereas Common Toads tend to prefer larger, deeper ponds in which to breed and deposit eggs. Although a pond is a good amphibian attractant, creating suitable terrestrial habitat throughout the garden is the key, as this is where amphibians will forage for slugs and other invertebrates outside of the breeding season (summer and autumn). Creating log piles and leaving unmown grass/scrub to grow in a mixture of shaded and sunny areas will provide cover from predators and maintain moisture, which amphibians are dependent on. Slow Worms will also benefit from this terrestrial habitat creation and in addition appreciate compost heaps – these maintain a warm temperature in which these legless lizards can thermoregulate. Compost heaps also provide an ideal protective place where the females can give birth.

April covers the breeding season for these species and encouraging them to reproduce in your garden will, over time, provide a population of slug predators. In addition, British reptiles and amphibians are rapidly declining – for example, the Common Toad has declined by 68% over the past 30 years (https://bit.ly/3ylPda9) so anything we can do to give them a helping hand should be done!

Tip 2: Plant Wildflowers

April is a great month to add nectar-rich wildflowers to your garden by creating a ‘wildflower strip’ in a sunny spot within the lawn!

Strip existing turf, removing all roots, and rake the seedbed to a fine tilth. Select a native wildflower seed mix suited to your soil type, sowing at approximately 2-4g/m2 to allow slower growing wildflowers space to establish amongst more vigorous grasses. Once sown, firm with your feet to ensure soil contact. When grasses reach 10cm, cut the vegetation, removing all cuttings to prevent increased soil nutrification, and remove any unwanted species. Throughout the first growing season, cut the area every 6-8 weeks (always removing the cuttings). From year two, cutting can be reduced to a spring cut in late March/early April and a second in late August/early September once flowers have set seed.

Alternatively, you could install ‘wildflower turf’ in your cleared strip, which contains established wildflowers and can be very effective. Management of wildflower turf should be undertaken as per the ‘year two’ advice above.

We would love to see how you get on, so please do tag us in your photos on social media!

May

Hold Fire Before Clearing Pond Duckweed

Duckweeds have a bad reputation for ‘ruining’ ponds due to their rapid growth and blanketing effect over the surface of the water, reducing light for other aquatic plants. However, when controlled, duckweeds can be highly beneficial to a pond ecosystem in several ways. There are five native species of duckweed in Britain: Common Duckweed, Ivy-leaved Duckweed, Great Duckweed, Fat Duckweed and Rootless Duckweed, which is among the world's smallest flowering plants.

Not only is duckweed a high protein meal for various waterfowl, but it also has the ability to reduce algal growth in a pond by utilising excess nutrients that would otherwise be consumed by algae, preventing large algal blooms. Agal blooms are more difficult to control than duckweed growth and severely reduce light penetration in the water. As duckweed removes nitrates from the water, it can be considered a water purifier. Furthermore, it provides important shelter for organisms that are vulnerable to predation, such as tadpoles.

However, due to its rapid growth rate, duckweed still requires some level of control if you want other aquatic plants to obtain enough light and flourish in the pond. This can be achieved by regular maintenance in the form of netting and raking to collect the duckweed for removal. To minimise damage to the ecosystem, it is best to rinse the removed duckweed in a bucket of pond water to separate any organisms that may be living in it. In case you’re wondering where to put it, duckweed can be added to a compost heap!

Go Peat Free

May is a great time of year for potting garden vegetables and wildflowers and is a time of year when garden centres sell a lot of substrate for this purpose.

‘Potting composts’ containing peat is usually sourced from the destruction of wild, live peat bogs – a highly vulnerable habitat that is home to specialist wildlife, such as an array of ground-nesting birds, specialist flora, butterflies, herpetofauna to name a few.

This habitat is virtually irreplaceable once destroyed due to the extremely slow process of peat formation. To put it into perspective, it can take 1,000 years to form a meter of peat (https://bit.ly/3ng934J). In addition, peat bogs are among the best carbon-sequestering habitats on earth and are key in combating the climate crisis.

Going peat-free in the products you purchase can go a long way in reducing the demand for peat extraction, relieving pressure on wild peat bog ecosystems. Unfortunately, products containing peat do not clearly state this and reading the small print is often required to find out if peat is in the product.

Many large horticultural institutions, including Kew Gardens, have massively reduced their peat use to almost zero and still maintain extraordinary botanical collections. Surely, we can maintain a peat-free or reduced-peat usage garden!

No Mow May

Most lawns are mown regularly to keep them neat and tidy. This can have benefits, such as controlling the growth of grasses which out-compete more sensitive wildflowers. However, it also reduces the availability of nectar-rich flowers for hungry invertebrates (and their availability up the food chain, as a foraging resource for species such as birds, reptiles and bats).

There’s no need to stop mowing entirely (unless you want to!), but why not consider following Plantlife’s superb No Mow May campaign? Create a veritable ‘pollen buffet’ during one of the most important months for our native invertebrates by allowing wildflowers to bloom in your lawn. Give your mower a rest, sit back and enjoy your garden bursting into colour, with species such as Selfheal, clover, daisies, Dovesfoot Cranesbill, trefoils, Germander Speedwell, buttercups, Yarrow and many more besides coming alive with insects. At the end of the month, put your botanical skills to the test by joining Plantlife’s Every Flower Counts survey, with your data contributing to nationwide conservation efforts!

Take a look at Plantlife's webpage for more details. We would also love to see how you get on, so please do drop us an email or tag us in your photos on social media!

June

Attract Nocturnal Pollinators to your Garden!

The Bramble (Rubus sp.) is often considered a gardener’s nightmare, but there is no denying that this plant is vital for a wide array of wildlife. The nectar-rich flowers and juicy Blackberries it produces through spring, summer and autumn provide a vital food source for various species throughout the seasons. Not to mention the dense cover it provides for nesting birds, herpetofauna, mammals and more. But have you ever thought about its benefit to nocturnal life?

University of Sussex researchers recently found that 83% of pollinator visits to Bramble flowers were made by diurnal insects, whereas nocturnal moths made only around 15% of the flower visits. This may seem like a mismatch, but this is where quality overrides quantity. Using remote camera technology to record the insects visiting Bramble flowers during the day and night, this research was able to calculate the speed in which pollination was occurring. The results showed that on these short summer nights the 15% of moth visitors pollinated at a significantly faster rate than the diurnal insects.

Not only does this support the importance of moth pollinators, but it also emphasises the importance of Bramble as a food source for moths at night.

Although the diurnal pollinators, some referred to as ‘busy bees’, are important, they tend to get a lot more credit than our nocturnal pollinators, which are, in fact, pollinating more efficiently.

With this in mind, leaving a small patch of Brambles in the garden can go a long way in keeping nocturnal ecosystems healthy.

Further info about the study can be found here: https://bit.ly/3BvPEjy

Original research paper: https://bit.ly/3IfKxrM

Supporting Bats

18 species of bat are found in the UK (17 of which breed here), accounting for nearly ¼ of all our mammal species, and you may well have seen some of them in your garden during warm summer evenings! Bats are fascinating, and there are plenty of things you can do to support them. Adding a pond is one of the best ways to attract bats to your garden; you’ll see them darting and diving over the water’s surface, feeding on the many winged invertebrates (a single Common Pipistrelle can eat up to 3,000 midges per night!). Adding plants with evening-scented flowers is also beneficial, as these attract insects such as moths at the time when hungry bats are just emerging from their roosts. Honeysuckle (native form: Lonicera periclymenum) is particularly effective!

July

Conserve Water for Wildlife

The drought of 2022 humbled many, in what is likely a symptom of the climate crisis. Water bodies were abnormally low, grasslands were scorched brown, fires were more frequent and the all-time hottest British temperature record was reached at a staggering 40.3⁰C on 19th July 2022. It is uncertain whether we will experience the same summer in 2023, but climate experts predict that hotter summers will become the norm. This is detrimental to wildlife due to effects such as ponds/rivers drying up, food becoming scarce, habitat destruction by fire and simply a lack of drinking water.

One of the best defences against drought for wildlife in your garden is investing in a water butt. Storing large quantities of rainwater in preparation for another potential drought can provide benefits such as being able to top up the garden pond, watering wild plants and providing drinking water for birds, mammals, insects and more. Remember to provide a way out of the container of any drinking water that you provide for the smaller animals in the form of branches, pebbles and other debris. The Wildlife Trust has provided useful information on how to install a water butt here: https://tinyurl.com/55hyy5d6

In addition, creating sheltered areas in the garden in the form of log, rock and/or vegetation piles can retain moisture during dry spells, aiding the survival of moisture-dependent animals, such as amphibians and invertebrates.

Bee hotels – gimmick or great wildlife feature?

Female solitary bees – as the name suggests – nest alone rather than in colonies, laying eggs in features like cracks in dry earth, hollow stems and old beetle holes. Bee hotels are usually made from bundled bamboo and logs with holes drilled into them, and are a wonderful resource for supporting solitary bees, who are vital pollinators for our gardens!

Although there are plenty of pre-made options, building your own bee hotel is a great Sunday afternoon project, especially with children. There are plenty of easy designs to follow online; ensure you use only untreated wood and provide a variety of tunnel diameters (approximately 2-6mm, to a depth of about 15cm), as different species have different preferences.

Location is key – position your bee hotel in full sun (south facing is best), fixed securely at chest height; a fence or wall is perfect. Ensure it is not obscured by any vegetation, but near to nectar-rich plants. With luck you will start noticing bees arriving with pollen in spring, as well as mud and/or leaves to line the tunnels and block the entrances (creating a ‘cell’). The grubs later hatch inside the cells, feed on the pollen and emerge as young bees the following year.

Add a bee hotel (or three!), position correctly, fill your garden with wildflowers and they will come!

August

Make Your Own Compost for a Healthier Environment

Making your own compost has a range of benefits, not just horticulturally, but environmentally as well. As you add organic material to your compost heap, it is broken down by a host of organisms from bacteria, fungi, worms and other invertebrates, which releases nutrients and enhances soil fertility. Using this compost is the best alternative to buying compost – not only because it’s free, but because there are no harmful chemicals or pesticides within it, which can be the case for some store-bought compost. This means that wild plants have a clean, nutritious substrate to grow in and animals associated with them will not be eating contaminated food.

Furthermore, the structure, temperature and humidity of a compost heap can provide an ideal microhabitat during important stages in the life cycle of species. For example, Britain’s largest native reptile, the Grass Snake (Natrix helvetica), will seek out such structures in which to lay its eggs. Slow Worms (Anguis fragilis) will also use compost heaps to give birth in and to thermoregulate. The humidity within the heap provides ideal shelter for moisture-dependent fauna such as amphibians, invertebrates and more.

So How do You Make Compost?

There are two main methods – Hot and Cold. ‘Hot composting’ involves collection of organic materials in an insulated compost bin such as a HOTBIN. The main benefit of hot composting is that it reaches 40°C – 60°C and so speeds up the process, breaking down organic matter in as little as 30 days. Furthermore, with hot composting, one can compost almost any organic matter (unlike regular composting) – so cooked food and garden waste can also be added. Cold composting is the same principle, just slower and is only able to process raw vegetable matter.

Teabags, a readily available source of organic waste in the UK, can be used in both hot and cold compost heaps. However, certain brands produce teabags containing plastic, which should be avoided. A guide to purchasing plastic-free teabags can be viewed here: https://www.zerowasted.co.uk/plastic-free-tea-bags

Finally, if more of us produce compost using our own organic waste, then the demand for peat will lessen. This will relieve pressure on peat extraction from wetlands, which ultimately destroys the habitat. Peaty wetlands are key in sequestering carbon and are home to rare and specialist species. And of course, reducing plastic packaging can only be a good thing!

Vertical Gardening

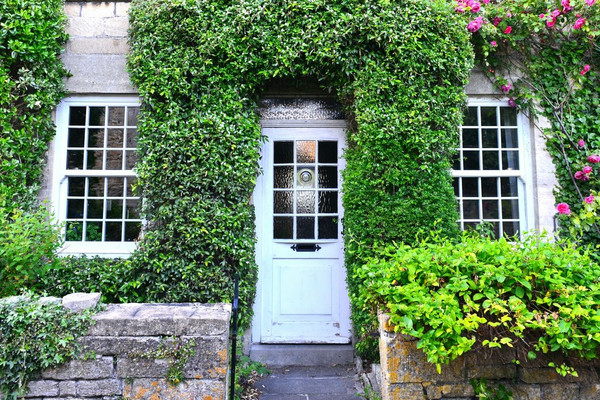

Do you have a small garden? Long lengths of fence? Buildings? If so, have you considered ‘vertical gardening’? This can be a wonderful way of adding ecological value to smaller spaces, as well as enhancing habitat connectivity.

You might consider encouraging Ivy to colonise fences – this is a fantastic resource for nesting birds, and the pollen attracts a plethora of insects. Honeysuckle, too, is a wonderful addition, its evening-scented flowers providing a veritable buffet for bats to feast upon!

Buildings, too, are often overlooked with regard to wildlife value, but these can provide a multitude of opportunities for enhancement of a site, such as adding bird and bat boxes, as well as insect hotels (check out last month’s tip for all things bug hotel!). Adding plants, particularly climbers, to walls can also reduce the ‘hot box’ effect of small, south-facing gardens, cooling the air and offering shade for wildlife.

September

Spare Ivy for Wildlife

During late summer and autumn, you may have noticed insects, in the form of bees, butterflies, wasps, flies and more, swarming around ivy bushes, mostly Common Ivy (Hedera helix) to be precise.

Ivy is a vital yet underappreciated source of food for insects, particularly in autumn as it is unusual among British plants in that it flowers at this time of year and even into November. To put the importance of autumnal ivy into numerical perspective, a University of Sussex study in 2013 found that 89% of pollen pellets collected by honeybees in the autumn were from ivy (https://bit.ly/3GtAu0e). Not only this, but ivy has specialist pollinator species that heavily depend on it late in the year, such as Ivy Bee (Colletes hederae) and Golden Hoverfly (Callicera spinolae). Ivy is also beneficial to vertebrate-life as its dark berries are consumed by various birds such as Redwing, Song Thrush, Blackbird, Starling, Blackcap and more.

Late-flying butterflies, such as Red Admirals (Vanessa atalanta), greatly benefit from this abundant nectar source when there is not much else around. Moths and butterflies often migrate at this time of year and depend on a nectar boost from ivy to power their flight. The leaves of ivy provide a foodplant for various moths and butterflies, including the second seasonal brood of Holly Blue (Celastrina argiolus). The adult butterfly also uses the flowers as a nectar source in late summer/autumn.

In addition to being a great food source for wildlife, the physical structure of ivy and the fact that it is evergreen creates ideal microclimates and shelter for hibernating/brumating invertebrates in the winter, as well as shelter for small mammals and birds during harsh weather conditions.

It is possible to control ivy growth in the garden while keeping it around so that wildlife can benefit from it. To maintain healthy ivy while doing this, it is best to prune it in late autumn/early winter after the flowers have died off and rotate the area of pruning on the ivy bush each year. However, the more ivy you can spare, the more wildlife will benefit from it!

Providing Winter Refuge for Wildlife

As long summer days begin the gradual transition into darker evenings and cooler temperatures, and our landscape explodes once again into a spectacular autumnal palette, much of our native wildlife starts to think about hibernation. Introducing a hibernaculum increases a garden’s biodiversity value by providing hibernating opportunities for a broad range of wildlife during the winter months (as well as offering valuable sheltering, breeding and foraging opportunities during active seasons).

An excellent hibernaculum can be created by digging a shallow hole – the bigger the better, but any size will add value – filling this with materials such as wood chip, rubble, rotting logs and gravel and then stacking logs of varying sizes on top, pointing in lots of different directions to create internal voids. Top the logs with brash, and then you might even cover the pile in turf (you could use wildflower turf for maximum value!), leaving areas uncovered to allow wildlife to access the pile’s internal voids. Situate this feature in a protected spot in partial sun to provide a range of internal temperatures, and make sure any materials used are inert to avoid adversely impacting wildlife or the surrounding environment.

October

Plant Native Shrubs in Autumn!

Native shrub-planting is best done in autumn, as the substrate is still at a mild temperature with a good level of moisture. This provides optimal conditions for the roots of shrubs to develop before the winter frost kicks in. By the time spring comes, the shrubs will be ready to flower and produce fruit next autumn, benefiting a wide array of wildlife throughout the seasons.

Shrub species that support a broad biodiversity include Blackthorn, Hazel, Hawthorn, Elder, Rowan and Crab Apple. These provide food for a range of taxa in the form of flowers, leaves and fruit. It is well known that this natural bounty attracts many birds, mammals and lepidoptera, including rarer species such as Hazel Dormouse (if connected to an existing hedgerow/woodland) and migratory rarities such as Waxwing.

Perhaps less known are the miniature predators that are attracted by the hundreds of insect species these plants support, such as the striking Green Crab Spider (Diaea dorsata). More information on the benefits of planting native shrubs, along with other native species, can be read here: https://tinyurl.com/6sttjb56

Thinking of planting some hedging over the winter months, or looking ahead to what you might like to add next season? Here are a few pointers to maximise ecological value:

- Aim for native species where possible, as these are best suited to our native wildlife.

- If non-native plants are preferred, choose high nectar and fruiting varieties, and those that are more attractive to pollinators – a single or semi-double rose with an open shape is more accessible than a densely-petalled or closed bloom.

- Wherever possible, source plants from locally-grown stock and species that are growing well in your local, wild areas – these will be better suited to local conditions and wildlife.

- Avoid plastic guards wherever possible! Some good, genuinely biodegradable alternatives are now available. Alternatively, use temporary fencing or brash piles to protect new plants from hungry visitors.

- Garden centres often have sections containing ‘wildlife friendly’ plants. Top tip – visit them on a sunny day to see which plants attract the most bees!

Where more than one plant of the same species is present, extend the flowering season by pruning at different times of year. For example, prune one Buddleia in November, and another in late February, to provide flowers throughout the summer and into the autumn as a valuable nectar source for butterflies.

November

Feed Birds the Right Food

As the coldest winter months approach, garden birds find it more difficult to find food. Throughout the winter, nutrient-rich invertebrate prey is mostly dormant and frost makes the ground hard, limiting access to worms and insect larvae. It is at this time of year when birds depend on feeders the most, so ensuring that you are providing the right food can give them a healthy boost to make it through to the following spring. High levels of protein, carbohydrates and unsaturated fat can be provided for birds in the form of sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, Nyjer seeds, suet balls and peanuts to name a few. Some of these foods are easy to grow at home, for example, in the form of the popular Sunflower. Some are preferred by certain species – for example, Nyjer seeds are a favourite of colourful species such as Goldfinch and Greenfinch, whereas peanuts tend to attract larger birds such as Great Spotted Woodpecker and Eurasian Jay, but also garden favourites such as the Nuthatch. More information about these foods and the benefits they provide to birds in winter can be viewed here: https://tinyurl.com/4hrn5dcr

Carry Out More Sustainable Gardening Practices

This month, as temperatures continue to drop and rainy days become more plentiful (great for topping up the pond!), put the kettle on and allow your thoughts to turn to how you might move to even more sustainable gardening practices next year. Here are a few suggestions:

- Choose plastic-free, fully biodegradable pots (coir, cardboard etc).

- Purchase responsibly-grown plants – organic (chemical free), locally grown (reduces road miles and better suited to local conditions) – or better yet, grow your own / allow for natural regeneration.

- Favour wildlife-friendly, organic herbicides and fertilisers such as home-made compost, sustainable seaweed feed and home-made fertiliser (soak Comfrey leaves in water in the sun for a few days – Comfrey is also a great nectar source for insects!). Use mulch and coir on flowerbeds rather than weed killer.

- Encourage insect-eating creatures such as amphibians, reptiles, hedgehogs and bats instead of using pesticides. Ladybirds, lacewings and hoverflies are excellent aphid controllers.

- Plant more plants! This draws down carbon from the atmosphere. Meadows offer excellent carbon sequestration.

- Grow your own food.

- Compost organic waste - sustainable compost with no road miles or packaging! This also reduces methane release from large landfills and creates on-site habitats.

- Install water butts for watering your garden, rather than using a mains-fed hose.

Every little helps – let us know how you keep your garden as sustainable as possible!

December

Make a Bird Feeder Using Plastic Waste

For something creative to do with the grandchildren (or, indeed, just yourself!), make a bird feeder from an empty plastic bottle. Approximately five million tonnes of plastic are used in the UK per year. Sadly, much of it will go to landfill where it will remain undecomposed or end up in our oceans, harming wildlife which then ingest it or get tangled in it. Much of this harmful waste is produced by supermarkets and, as a consumer, it can be difficult to avoid. So why not try to put some of that waste to good use? Plastic is highly durable, which makes it an ideal material for building bird feeders! All you need is a plastic bottle with the cap (or a similar structure), two sticks, a pin, scissors and string. The Natural History Museum has made this useful demonstration video on how to assemble a homemade bird feeder: https://tinyurl.com/bdf82wmb. Remember to ensure that any holes in the plastic are smooth-edged to avoid feathers snagging. If you’re unsure what to fill your homemade bird feeder with, then take a look at our previous November Gardening for Wildlife Tip.

Plant Bare Root Whips

December is a great month to enhance your garden for wildlife! Bare root whips (young saplings) are a cost-effective way to introduce scrub, copses and hedgerows. Include a broad range of native species to extend the flowering and fruiting period, ideally throughout the whole year. Species like Willow and Blackthorn provide early nectar sources; Hawthorn, Bramble and Rose offer summer flowers and autumn fruit; and Ivy offers autumn nectar and late winter berries. Honeysuckle adds additional structure, habitat opportunities and evening-scented flowers (attracting winged invertebrates – great for foraging bats!).

Loading search...

Loading search...